Traiter des douleurs chroniques est compliqué. La médecine propose des traitements antalgiques précis pour arriver à moduler la douleur. Généralement, elle met en place un traitement pluridisciplinaire pour mieux maîtriser l'évolution de la maladie. Actuellement, on considère les douleurs chroniques comme de véritables maladies.

L'activité physique adaptée est recommandée pour lutter contre les douleurs chroniques. La thérapie manuelle est conseillée en association aux traitements médicaux classiques.

En Posturopathie, la prise en charge des douleurs chroniques passe par une éducation du patient dans la compréhension du fonctionnement de la douleur. Ce procédé est largement utilisé en Thérapeutic Neuroscience Education. Toute thérapie a un effet placebo. Répondre aux attentes du patient et prendre le temps de relativiser le sens de la douleur en lui expliquant son mode de fonctionnement est un atout thérapeutique aujourd’hui largement démontré. L'article suivant illustre bien le cas d'une proposition en Thérapeutique Neuroscience Education.

La technique instrumentale Posturopathique (TIP) traite les douleurs chroniques. Elle propose un traitement spécifique de désensibilisation périphérique et centrale de la douleur. Lors de son application, le praticien passe par une phase d'éducation du fonctionnement de la douleur auprès du patient pour qu'il comprenne pourquoi la TIP doit lui amener une guérison à court terme.

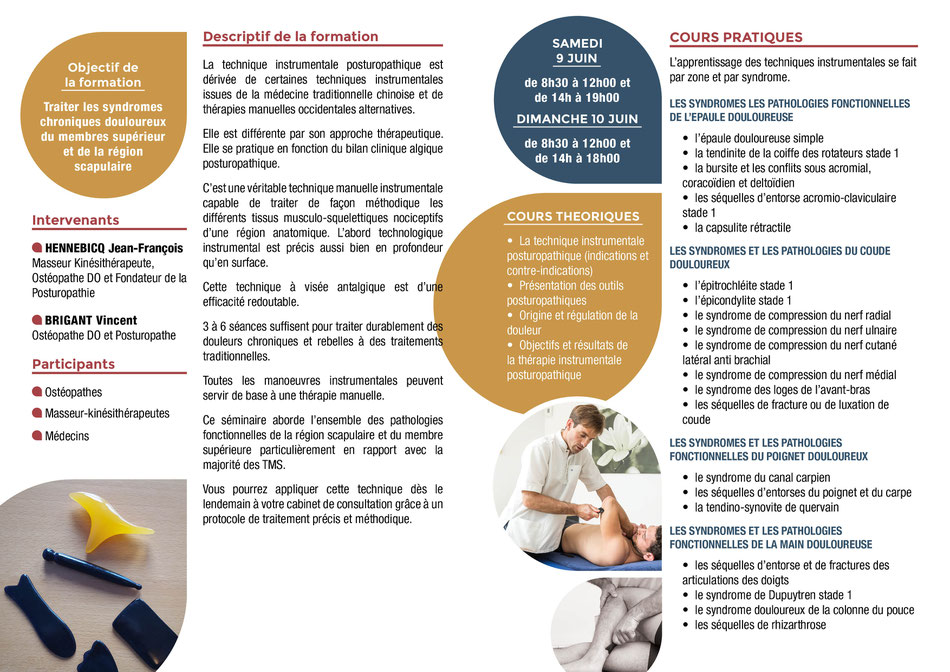

Le séminaire du 9-10 juin 2018 sur l'apprentissage de la technique instrumentale posturopathique concernant le traitement des douleurs chroniques et des TMS du membre supérieur peut vous permettre de découvrir une nouvelle méthode de soin dans l'esprit de la Thérapeutic Neuroscience Education.

Inscrivez vous sur www.posturopathie-institut.com.

Bonne lecture

Teaching People About Pain

Pain is a normal human experience. Without the ability to experience pain, people would not survive. Living in pain, however, is not normal.1 Pain that lasts beyond the normal healing time of tissues is called chronic or persistent pain. Worldwide, chronic pain is increasing. In the US alone, chronic pain has doubled in the last 15-20 years.2 With this increase, comes increased cost. Within Medicare, a US government-based insurance, epidural steroid (pain) injections have increased 629% in the last five years and the use of opioids (for example, hydrocodone and oxycodone) is up 423%.1 This increase is not isolated to the US and represents a global concern. In the shadow of this growing epidemic, we are faced with serious questions. Why is chronic pain increasing? Why are some of our most heroic treatments (opioids, injections, surgery, amputations, etc.) not working? The answer to these questions is complex and contains a variety of issues.

Over the last 10 years, our research team (International Spine and Pain Institute; Therapeutic Neuroscience

Research Group) has explored one such potential cause and set in motion a variety of research projects aimed at teaching people more about pain.3

Traditional medicine is strongly rooted in a biomedical model.4, 5 The biomedical model assumes that injury and pain are the same issue; therefore, an increase in pain means increased tissue injury and increased tissue issues lead to more pain. This model (called the Cartesian model of pain) is over 350 years old, and it's incorrect.1

Compounding the issue, the tissue model is then also used to teach patients why they hurt. For example, a

patient presents at the clinician’s office with low back pain that significantly limits his function and movement. In this scenario, the clinician grabs the nearest spine model and explains

to the patient that the reason he is hurting is due to a “bad disc” or “certain abnormal or faulty movement.” Now the model is set in place: correct the faulty tissue or movement and pain

will go away.6 Not only does this model not

work, but it actually increases fear and anxiety. Words like "bulging," "herniated," "rupture" and "tear" increase anxiety and make people less interested in movement, which is essential for

recovery. Our research team contends that this approach contains a blatant flaw. When people seek treatment for pain, why teach them about joints and muscles? We should teach them about pain.

This approach of teaching people about joints when they have pain does not make sense, and in fact does not answer the big question: Why do I hurt?7 This is especially true when pain persists for long

periods; we know most tissues in the human body heal between 3-6 months.1 It is now well established that ongoing pain is more due

to a sensitive nervous system. In other words, the body’s alarm system stays in alarm mode after tissues have healed.8

Our research has shown that people in pain are interested in pain, especially in regard to how pain

works.9 Learning the biological processes of

pain is called neuroscience education (the science of nerves). Since educating people about the science of nerves in regards to pain has a positive therapeutic effect, we decided to use the

term Therapeutic Neuroscience Education (TNE). Based on a large number of high-quality studies, it has been shown that teaching people with

pain more about the neuroscience of their pain (TNE) produces some impressive immediate and long-term changes.1, 3, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16

- Pain decreases

- Function improves

- Fear diminishes

- Thoughts about pain are more positive

- Knowledge of pain increases

- Movement improves

- Muscles work better

- Patients spend less money on medical tests and treatments

- The brain calms down, as seen on brain scans

- People are more willing to do much-needed exercise

How and why does this work? First, therapeutic neuroscience education changes a patient’s perception of pain. Originally, a patient may have believed that a certain tissue was the main cause for their pain. With TNE, the patient understands that pain may not correctly represent the health of the tissue, but may be due to extra-sensitive nerves. Second, fear is eased, and the patient is more able and willing to move and exercise.

How do we do it? This is the fun part. Every time we show people what we do, we get nervous—it seems so simple. We have developed a way to take very complex processes of the nerves and brain and make them easy to understand. Once we have distilled the information into an easy-to-understand format and paired it up with some interesting visuals, it becomes easy for everyone to understand. This includes patients of all ages, education levels, ethnic groups, etc. Using interpreters, TNE can be used all around the world.

Here's a brief example of therapeutic neuroscience education in practice: Suzy is experiencing pain and believes her pain is due to a bad disc. However, the pain has been there for 10 years. It is well established that discs reabsorb between 7-9 months and completely heal.17,18, 19, 20, 21 So, why would it still hurt? She believes (as she has been told by clinicians) that her pain is caused by a bad disc. Now, we start explaining complex pain issues via a story/metaphor with the aim to change her beliefs, and then we set a treatment plan in place based on the new, more accurate neuroscience view of pain.

Therapist: “If you stepped on a rusted nail right now, would you want to know about it?”

Patient: “Of course.”

Therapist: “Why?”

Patient: “Well; to take the nail out of my foot and get a tetanus shot.”

Therapist: “Exactly. Now, how do you know there’s a nail in your foot? How does the nail get your attention?”

Therapist: “The human body contains over 400 nerves that, if strung together, would stretch 45 miles. All of these nerves have a little bit of electricity in them. This shows you’re alive. Does this make sense?”

Patient: “Yes.”

Therapist: “The nerves in your foot are always buzzing with a little bit of electricity in them. This is normal and shows….?”

Patient: “I’m alive.”

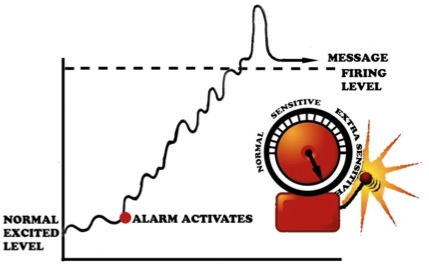

Therapist: “Yes. Now, once you step on the nail, the alarm system is activated. Once the alarm’s threshold is met, the alarm goes off, sending a danger message from your foot to your spinal cord and then on to the brain. Once the brain gets the danger message, the brain may produce pain. The pain stops you in your tracks, and you look at your foot to take care of the issue. Does this sound right?”

Image from: Why Do I Hurt? Louw (2013 OPTP – with permission)

Patient: “Yes.”

Therapist: “Once we remove the nail, the alarm system should…?”

Patient: “Go down.”

Therapist: “Exactly. Over the next few days, the alarm system will calm down to its original level, so you will still feel your foot for a day or two. This is normal and expected."

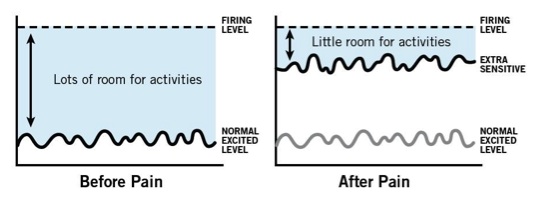

Therapist: “Here’s the important part. In one in four people, the alarm system will activate after an injury or stressful time, but never calm down to the original resting level. It remains extra sensitive. With the alarm system extra sensitive and close to the “firing level,” it does not take a lot of movement, stress or activity to activate the alarm system. When this happens, surely you think something MUST be wrong. Based on your examination today, I believe a large part of your pain is due to an extra-sensitive alarm system. So, instead of focusing of fixing tissues, we will work on a variety of strategies to help calm down your alarm system, which will steadily help you move more, experience less pain and return to previous function."

The example above is just one story/metaphor we use to teach patients about complex processes like injury, inflammation, nerves waking up, extra-sensitive nerves, brain processing information, pain produced by the brain, etc. It seems quite simple, but it's complex. The crucial part is that patients are easily able to understand the example and better yet, the principle. Subsequently, a significant shift occurs. Instead of only seeing pain from a “broken tissue” perspective, they see pain from a sensitive nervous system perspective. Simply stated, they understand they may have a pain problem rather than a tissue problem. Now, the fun starts. If you're the fifth therapist a chronic pain patient has seen, he or she will likely have little hope that you will be able to help, since your treatment will likely be the same as the others. This neuroscience view of sensitive nerves versus tissue injury allows for a new, understandable view of treatments aimed at easing nerve sensitivity, such as aerobic exercise, manual therapy, relaxation, breathing, sleep hygiene, diet and more.

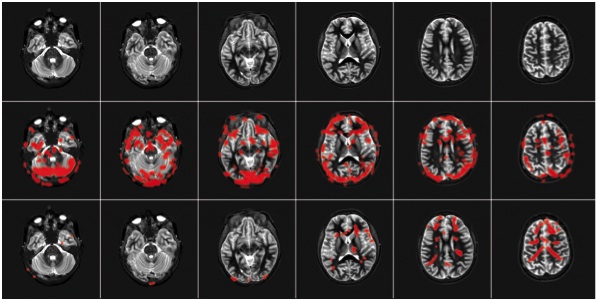

When a patient learns more about pain and how pain works, their pain eases considerably and they experience a variety of other benefits, such as increased movement, better function and less fear. These effects are measurable and we believe they can do more than some of the most powerful drugs in the world, without any of the side-effects. Look at the picture below (Louw A, et. al 2014 – submitted for publication). It’s a brain scan we performed on a high-level dancer experiencing significant back pain for almost two years. She was scheduled for back surgery in two days and was nervous and anxious.

Row 1: She was in the scanner, relaxing and watching a movie. You will notice you there are no red "blobs."

Row 2: We asked her to move her painful back while in the scanner. The scanner picks up activity of the brain and displays it as red blobs. Without being too technical, the more red blobs we see, the more pain she was experiencing. Therefore, Row 2 shows her brain while she is having pain during spine movements.

Row 3: After Row 2’s scans (red blobs), we took her out of the scanner and spent 20-25 minutes teaching her more about pain, as we describe earlier. After the education session, we re-scanned her brain doing the same painful task as performed in Row 2. This time, however, there is significantly less activity, fewer red blobs, while doing the same painful task as before.

This is a graphic representation of how teaching people about pain helps ease pain. It works. Know pain; know gain.

Author

Adriaan Louw, PT, PhD, CSMT

References

1. Louw, A. & Puentedura, E. J. (2013). Therapeutic Neuroscience Education, Vol. 1. Minneapolis, MN: OPTP.

2. Johannes, C. B., Le, T. K., Zhou, X., Johnston, J. A., & Dworkin, R. H. (2010). The prevalence of chronic pain in United States adults: Results of an internet-based survey. Journal of Pain, 11(11), 1230-1239.

3. Louw, A., Diener, I., Butler, D. S., & Puentedura, E. J. (2011). The effect of neuroscience education on pain, disability, anxiety, and stress in chronic musculoskeletal pain. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 92(12), 2041-2056.

4. Louw, A., & Butler, D. S. (2011). Chronic back pain and pain science. In Brotzman, S. B. & Manske, R. (eds.), Clinical Orthopaedic Rehabilitation, 3rd Edition (pp. 498-506). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

5. Louw, A., Diener, I., Butler, D. S., & Puentedura, E. J. (2013). Preoperative education addressing postoperative pain in total joint arthroplasty: Review of content and educational delivery methods. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 29(3),175-194.

6. Haldeman, S. (1990). Presidential address, North American Spine Society: Failure of the pathology model to predict back pain. Spine, 15(7), 718-724.

7. Gifford, L. S. (1998). Pain, the tissues and the nervous system. Physiotherapy, 84, 27-33.

8. Louw, A., Butler, D. S., Diener, I., & Puentedura, E. J. (2013). Development of a preoperative neuroscience educational program for patients with lumbar radiculopathy. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 92(5), 446-452.

9. Louw, A., Louw, Q., & Crous, L. C. (2009). Preoperative education for lumbar surgery for radiculopathy. South African Journal of Physiotherapy, 65(2), 3-8.

10. Zimney, K., Louw, A., & Puentedura, E. J. (2014). Use of Therapeutic Neuroscience Education to address psychosocial factors associated with acute low back pain: A case report. Physiotherapy: Theory and Practice, 30(3), 202-209.

11. Louw, A., Puentedura, E. L., & Mintken, P. (2012). Use of an abbreviated neuroscience education approach in the treatment of chronic low back pain: A case report. Physiotherapy: Theory and Practice, 28(1), 50-62.

12. Moseley, G. L. (2002). Combined physiotherapy and education is efficacious for chronic low back pain. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 48(4), 297-302.

13. Moseley, G. L., Hodges, P. W., & Nicholas, M. K. (2004). A randomized controlled trial of intensive neurophysiology education in chronic low back pain. Clinical Journal of Pain, 20, 324-330.

14. Moseley, G. L. (2004). Evidence for a direct relationship between cognitive and physical change during an education intervention in people with chronic low back pain. European Journal of Pain, 8, 39-45.

15. Meeus, M., Nijs, J., Van Oosterwijck, J., Van Alsenoy, V., & Truijen, S. (2010). Pain physiology education improves pain beliefs in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome compared with pacing and self-management education: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 91(8), 1153-1159.

16. Moseley, G. L. (2005). Widespread brain activity during an abdominal task markedly reduced after pain physiology education: fMRI evaluation of a single patient with chronic low back pain. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 51(1), 49-52.

17. Autio, R. A., Karppinen, J., Niinimaki, J., et al. (2006). Determinants of spontaneous resorption of intervertebral disc herniations. Spine, 31(11), 1247-1252.

18. Komori, H., Okawa, A., Haro, H., Muneta, T., Yamamoto, H., & Shinomiya, K. (1998). Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in conservative management of lumbar disc herniation. Spine, 23(1), 67-73.

19. Komori, H., Shinomiya, K., Nakai, O., Yamaura, I., Takeda, S., & Furuya, K. (1996). The natural history of herniated nucleus pulposus with radiculopathy. Spine, 21(2), 225-229.

20. Masui, T., Yukawa, Y., Nakamura, S., et al. (2005). Natural history of patients with lumbar disc herniation observed by magnetic resonance imaging for minimum 7 years. Journal of Spinal Disorders & Techniques, 18(2), 121-126.

21. Yukawa, Y., Kato, F., Matsubara, Y., Kajino, G., Nakamura, S., & Nitta, H. (1996). Serial magnetic resonance imaging follow-up study of lumbar disc herniation conservatively treated for average 30 months: Relation between reduction of herniation and degeneration of disc. Journal of Spinal Disorders, 9(3), 251-256.

Date of publication: May 26, 2015

Écrire commentaire